Good day, dear readers! I hope you have enjoyed the last three posts in this series on creatures that are commonly (if not necessarily accurately) referred to as “living fossils”. If not, while not required to appreciate this post, I suggest reading Parts I, II, and III first, which examined such things as stromatolites, plants, monotremes, birds and mammals. Today’s offerings will include reptiles and amphibians.

Let’s start with perhaps one of the more famous animals in this list, the tuatara.

A frequent inclusion on listicles about “living fossils”, the tuatara is famed because of how unique a creature it is. Despite its appearance, it is not a lizard; it is a reptile, but not a lizard. Specifically, it’s a rhynchocephalian, the only member of order Rhynchocephalia. Its order is a sister to Squamata (lizards & kin), but it is a genetically distinct creature from a different lineage than lizards. It also differs from lizards in its preference for cooler temperatures, nocturnalness, its lack of external ears and its unusual dentition: instead of having just one row of teeth in each jaw, the tuatara has two rows of teeth in its upper jaw, which overlaps a single row in the lower jaw.

One of its most interesting features is not something unique to tuataras: its parietal eye, sometimes referred to as its “third eye”. Parietal eyes sit on the top of the head or on the forehead of a number of different reptiles, amphibians, and fish, and have different levels of functionality; however, this “eye” is most well-developed in tuataras. In other creatures, it’s sometimes visible as a gray scale or patch on the head; in tuataras, it’s only externally visible in the young, as it is covered with scales and pigment as they mature. Despite this, the parietal eye does receive and perceive light, which helps govern their circadian rhythm, hormones and temperature regulation.

Next we’re going to be speaking of salamanders, but I wanted to interrupt with a brief purple frog interlude.

It is my pleasure to introduce you to the very good purple frog (Nasikabatrachus sahyadrensis), also known as the pignose frog or the Indian purple frog. In addition to being pleasing to look upon, they’re one of only two species in their family Nasikabatrachidae. They are burrowing frogs that spend the majority of their lives underground, which does not make them especially easy to study. Unfortunately, they’re also listed as endangered on the IUCN Redlist due their habitats being turned into areas of agricultural cultivation.

But you know now that they exist (if you didn’t previously – their goofy appearance has caused them to pop up in memes and the like) and knowing is half the battle.

Our next featured creature are the giant salamanders, all of which live in east Asia (the Chinese and Japanese giant salamanders), except for eastern North America’s very own hellbender (as depicted above). The world’s largest amphibians, the Chinese giant salamander has been recorded reaching a maximum length of 5.9 ft (1.8 m), while the Japanese giant salamander comes in second at lengths of up to 4.7 ft (1.44 m). Comparatively, hellbenders are the fourth-largest amphibians in the world, growing up to 2.4 ft (73.6 cm), after the goliath frog (12.6 inches/32 cm, 7.17 lbs/3.25 kg).

One of their unique features is their form of respiration: the frilly skin on their sides behave like gills. Unfortunately, their conservation statuses are precarious: while hellbenders and the Japanese giant salamander are near-threatened, the Chinese giant salamander is critically endangered due to habitat destruction, habitat degradation and human exploitation.

While it’s still too early to see conclusive results, attempts are being made by the World Conservation Society in conjunction with the Buffalo and Bronx Zoos to carefully raise young hellbenders from eggs to an age where they can be released with greater chance of survival into adulthood in their native habitats.

If you’re interested in hellbender conservation efforts, Dr. Peter Petokas of the Clean Water Institute (CWI) at the Department of Biology at Lycoming College in Williamsport, Pennsylvania has information both on his own personal site and on the CWI’s conservation project page.

Speaking of hellbenders and Pennsylvania, in 2017 the legislative process to designate the eastern hellbender the official state amphibian of Pennsylvania began. Its journey to this lofty status is thus far incomplete, but be assured that we here at the Free-for-All will keep you abreast of the latest developments.

Next, I am proud to present one of the more charismatic living (not) fossils, the axolotl, also probably the most charismatic amphibian and salamander. QUICK AXOLOTL FACTS:

- Axolotls are neotonous salamanders (meaning they can reach maturity without undergoing metamorphosis; alternatively, that they continue to exhibit juvenile traits in adulthood)

- Despite their neotony, they can be artificially forced through metamorphosis.

- They live wild in a single lake and canal complex (Xochimilco, a UNESCO World Heritage Site) in Mexico.

- They are critically endangered in the wild. This is bad; here (Scientific American) are some (PBS) articles about this (Smithsonian Magazine).

- The branches extending from their heads are not for decoration: those are their gills.

- As of January 2018, their genome is the largest to have been decoded (at 32 million base pairs, it’s ten times larger than the human genome). The work was accomplished by a team from the Heidelberg Institute for Theoretical Studies at the DRESDEN Concept Genome Center. Here’s

- Despite the high proportion of images you’ll encounter online of light-colored captive axolotls, they come in a range of shades.

- They are popular pets! Axolotl.org and the caudata.org axolotl forums are happy to field all your questions about axolotl care and maintenance. Please note that they are not legal to keep in all U.S. states, so please check with your state’s department of fish, wildlife and game before purchasing.

Even among salamanders, axolotls’ regenerative abilities are outstanding. For this reason, they’re an important research subject. Here’s a quote from Professor Stephane Roy at the University of Montreal:

You can cut the spinal cord, crush it, remove a segment, and it will regenerate. You can cut the limbs at any level—the wrist, the elbow, the upper arm—and it will regenerate, and it’s perfect. There is nothing missing, there’s no scarring on the skin at the site of amputation, every tissue is replaced. They can regenerate the same limb 50, 60, 100 times. And every time: perfect.

While perhaps not as exotic, charismatic, or strange-looking as some of the animals I’ve profiled, but one cannot neglect the crocodilians, for they most certainly qualify as living fossils. The term “crocodilians” refers to members of order Crocodilia; in more lay-friendly terms, it broadly includes the crocodiles, the alligators and the gharials. Don’t worry, I didn’t forget caimans – they fall under family Alligatoridae, making them alligatorids.

The big question: what’s the difference between alligators and crocodiles? Are they the same? The answer is no, they’re different, and here is why. There’s even (relatively) breaking news about further differences observed between these two families of crocodilians.

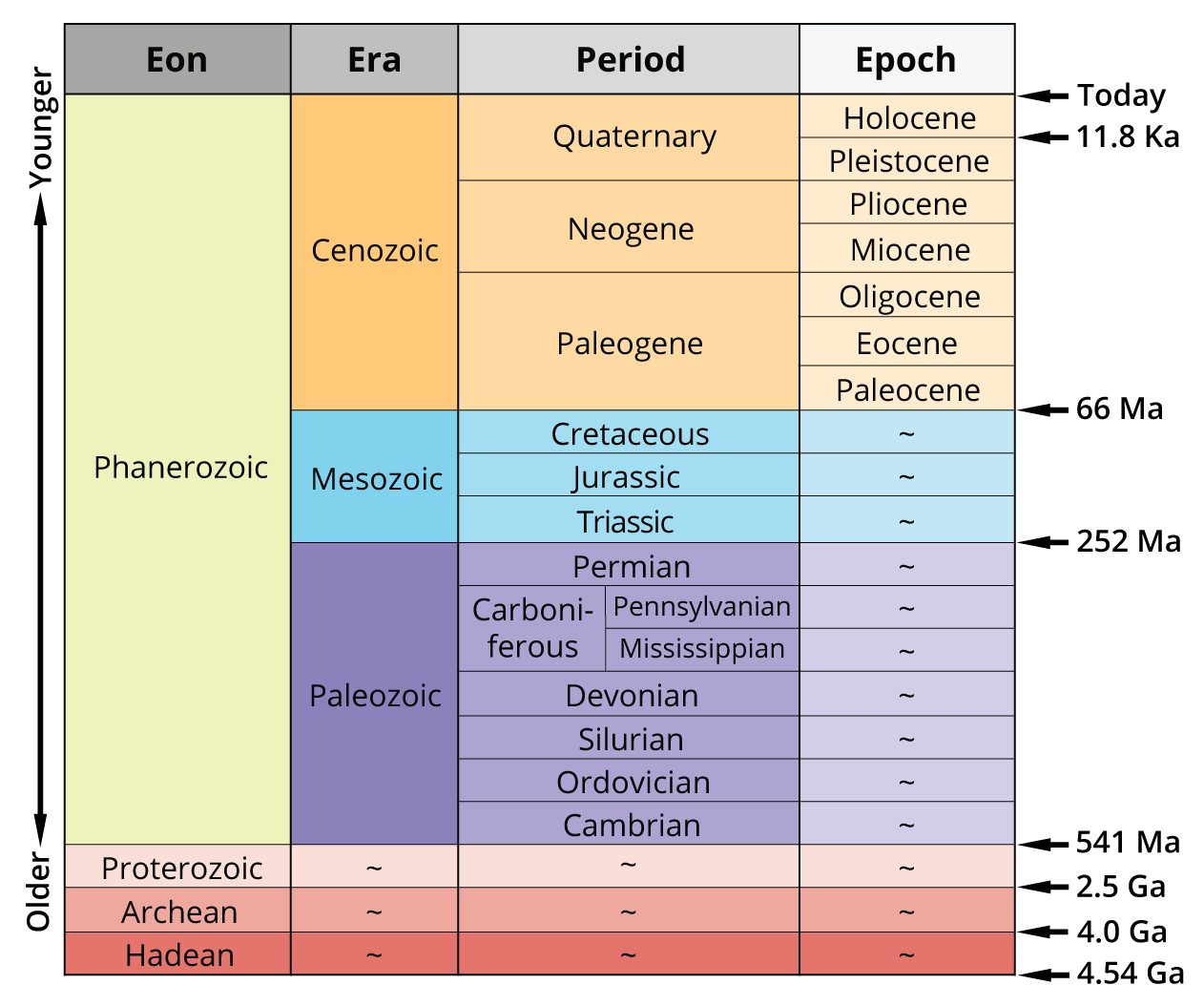

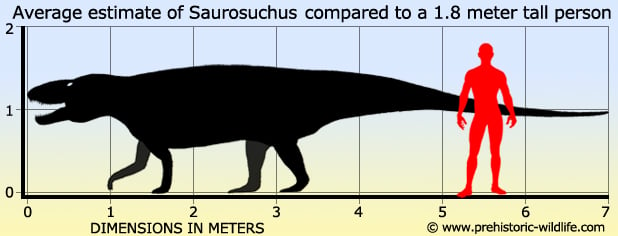

So how old are the crocodilians as a group? Their ancestors show up in the fossil record some 200 million years ago, at the end of the Triassic period. In March of 2017, the BBC reported on the discovery of 152 million-year-old crocodilian eggs in Portugal that were laid during the late Jurassic period. Curiously, the eggs were discovered in a dinosaur nest. Perhaps the most famous extinct crocodilian ancestor was the massive Saurosuchus of the Cretaceous, a 23 ft. (7 m) carnivore and the largest paracrocodylomorph on record.

Together, the crocodilians (living and extinct) and birds (living and extinct) form the clade group Archosauria, which includes the most recent common ancestor of both birds and crocodilians. This also means that the crocodilians are the closest living relatives of birds.

Which raises the question: since we’re talking about dinosaurs, crocodiles and birds – what is a dinosaur? The public has the habit of talking about any extinct reptile (or less charitably, people of a certain age) as a “dinosaur”. To clarify this complicated topic, the Smithsonian has an article about what exactly scientifically qualifies a dinosaur as a dinosaur (fun fact: all birds are dinosaurs, but not all dinosaurs are birds) .

All this raises yet another question: if dinosaurs are reptiles, and birds are dinosaurs, does that mean that birds are reptiles? The science question hotlines at Arizona State University and at the University of California at Santa Barbara explain things simply, but if you want to get into a somewhat Nietzschean discussion of taxonomic arcana (and who doesn’t?), here’s an article about why reptiles aren’t a thing anymore.

Circling back around from our shark week entries (parts I and II), I wanted to mention the star of Shark Week 2018 (at least in the land of Fish Twitter, where I happily lurk), marine biologist Melissa Cristina Márquez, who was attacked and dragged by a crocodile while searching for a legendary local shark in Cuba. She’s big in the science communication field (#scicomm! Check out that hashtag on the social media platforms of your choice!), founded the Fins United Initiative and hosts the podcast ConCienca Azul, which focuses on “….interviewing Spanish-speaking marine scientists, conservationists, grad students, photographers, and more from around the world” in Spanish.

PUBLIC SERVICE ANNOUNCEMENT

We interrupt this post with this message from our local hosting library: Do you not speak, read, write or understand Spanish? Or least not as well as you’d like to? Need to brush up on old skills? The PIL can help – in addition to physical language learning materials in our collection, the library subscribes to the Pronunciator collection of language learning resources. Simply log in with your PIL card and start studying one (or more!) of over 80 different languages today, including English as a Second Language in many languages of instruction, on your desktop, laptop or device!

Let’s conclude today’s entry today as we traditionally do: with book recommendations! I think one or two may be a repeat, but perhaps that simply means the books are twice as sweet.

Crocodile: Evolution’s Greatest Survivor, by Lynne Kelly

Following the fascinating history of the crocodile, this story tells the tale of an ancient animal whose ancestors have roamed the earth since the time of the dinosaurs. Addressing the true nature of this intriguing animal, this resource explores its evolutionary survival, the 23 living species in the world today, and the extinction they face due to habitat intrusion. Also explored are the myths and legends surrounding crocodiles and the vicious reputation they have amongst humans.

Frogs are worshipped for bringing nourishing rains, but blamed for devastating floods. Turtles are admired for their wisdom and longevity, but ridiculed for their sluggish and cowardly behavior. Snakes are respected for their ability to heal and restore life, but despised as symbols of evil. Lizards are revered as beneficent guardian spirits, but feared as the Devil himself.

In this ode to toads and snakes, newts and tuatara, crocodiles and tortoises, herpetologist and science writer Marty Crump explores folklore across the world and throughout time. From creation myths to trickster tales; from associations with fertility and rebirth to fire and rain; and from the use of herps in folk medicines and magic, as food, pets, and gods, to their roles in literature, visual art, music, and dance, Crump reveals both our love and hatred of amphibians and reptiles—and their perceived power. In a world where we keep home terrariums at the same time that we battle invasive cane toads, and where public attitudes often dictate that the cute and cuddly receive conservation priority over the slimy and venomous, she shows how our complex and conflicting perceptions threaten the conservation of these ecologically vital animals.

Sumptuously illustrated, Eye of Newt and Toe of Frog, Adder’s Fork and Lizard’s Leg is a beautiful and enthralling brew of natural history and folklore, sobering science and humor, that leaves us with one irrefutable lesson: love herps. Warts, scales, and all.

The Bare Bones: An Unconventional Evolutionary History of the Skeleton, by Matthew F. Bonnan

Since I’m spending quite a bit of time talking about evolution, I figured this could be an interesting text to our readers. What can we learn about the evolution of jaws from a pair of scissors? How does the flight of a tennis ball help explain how fish overcome drag? What do a spacesuit and a chicken egg have in common? Highlighting the fascinating twists and turns of evolution across more than 540 million years, paleobiologist Matthew Bonnan uses everyday objects to explain the emergence and adaptation of the vertebrate skeleton. What can camera lenses tell us about the eyes of marine reptiles? How does understanding what prevents a coffee mug from spilling help us understand the posture of dinosaurs? The answers to these and other intriguing questions illustrate how scientists have pieced together the history of vertebrates from their bare bones. With its engaging and informative text, plus more than 200 illustrative diagrams created by the author, The Bare Bones is an unconventional and reader-friendly introduction to the skeleton as an evolving machine.

Dinosaurs, with their awe-inspiring size, terrifying claws and teeth, and otherworldly abilities, occupy a sacred place in our childhoods. They loom over museum halls, thunder through movies, and are a fundamental part of our collective imagination. In My Beloved Brontosaurus, the dinosaur fanatic Brian Switek enriches the childlike sense of wonder these amazing creatures instill in us. Investigating the latest discoveries in paleontology, he breathes new life into old bones.

Switek reunites us with these mysterious creatures as he visits desolate excavation sites and hallowed museum vaults, exploring everything from the sex life of Apatosaurus and T. rex‘s feather-laden body to just why dinosaurs vanished. (And of course, on his journey, he celebrates the book’s titular hero, “Brontosaurus“—who suffered a second extinction when we learned he never existed at all—as a symbol of scientific progress.)

With infectious enthusiasm, Switek questions what we’ve long held to be true about these beasts, weaving in stories from his obsession with dinosaurs, which started when he was just knee-high to a Stegosaurus. Endearing, surprising, and essential to our understanding of our own evolution and our place on Earth, My Beloved Brontosaurus is a book that dinosaur fans and anyone interested in scientific progress will cherish for years to come.

Turtles All the Way Down, by John Green

Why feature this book? Turtles All the Way Down features the rare character of a tuatara (named “Tua”) in a work of fiction. 16-year-old Aza never intended to pursue the mystery of fugitive billionaire Russell Pickett, but there’s a hundred-thousand-dollar reward at stake and her Best and Most Fearless Friend, Daisy, is eager to investigate. So together, they navigate the short distance and broad divides that separate them from Russell Pickett’s son, Davis.

Aza is trying. She is trying to be a good daughter, a good friend, a good student, and maybe even a good detective, while also living within the ever-tightening spiral of her own thoughts.

In his long-awaited return, John Green, the acclaimed, award-winning author of Looking for Alaska and The Fault in Our Stars, shares Aza’s story with shattering, unflinching clarity in this brilliant novel of love, resilience, and the power of lifelong friendship.

The Book of Barely Imagined Beings: A 21st Century Bestiary, by Caspar Henderson

(If you look down in the bottom left corner of the cover, you can see the smiling face of an axolotl.) From medieval bestiaries to Borges’s Book of Imaginary Beings, we’ve long been enchanted by extraordinary animals, be they terrifying three-headed dogs or asps impervious to a snake charmer’s song. But bestiaries are more than just zany zoology—they are artful attempts to convey broader beliefs about human beings and the natural order. Today, we no longer fear sea monsters or banshees. But from the infamous honey badger to the giant squid, animals continue to captivate us with the things they can do and the things they cannot, what we know about them and what we don’t.

With The Book of Barely Imagined Beings, Caspar Henderson offers readers a fascinating, beautifully produced modern-day menagerie. But whereas medieval bestiaries were often based on folklore and myth, the creatures that abound in Henderson’s book—from the axolotl to the zebrafish—are, with one exception, very much with us, albeit sometimes in depleted numbers. The Book of Barely Imagined Beings transports readers to a world of real creatures that seem as if they should be made up—that are somehow more astonishing than anything we might have imagined. The yeti crab, for example, uses its furry claws to farm the bacteria on which it feeds. The waterbear, meanwhile, is among nature’s “extreme survivors,” able to withstand a week unprotected in outer space. These and other strange and surprising species invite readers to reflect on what we value—or fail to value—and what we might change.

Until next time dear readers!