Welcome back to the Stage of Fish, dear readers! Today I will conclude what I started last week: talking about batoids, aka shark relatives! In particular, I’ll be talking about stingrays, manta rays and electric rays.

Stingrays have long had a reputation for being dangerous. This is probably because they have venom-coated barbs on their tails that they will stab you in the leg with if you stomp on them.

However, due to the tragic and unusual death of nature television show star Steve Irwin at the tail of a stingray, reactions to them seem to have to turned to outright fear: while one should never give too much credence to YouTube comments or anything they read on Yahoo! Answers, I have seen far too many comments on batoid-centric videos that called every batoid a “stingray” and treated every “stingray” like it’s a vicious predator out to get them. This is actually the same way many people tend to talk about sharks, which is also grossly inaccurate, misinformed and has led to negative repercussions for that much-put-upon fish.

FACTS:

When a stingray wounds a human, it is out of self-defense, not malice. I personally think that stabbing whatever creature that is exponentially larger and heavier than me and happens to be standing on my cartilaginous body is a perfectly valid reason for exercising a typically non-lethal defense mechanism. When you are playing at the beach, please remember that you are in their habitat, not vice versa. Also:

Humans are not a food source for stingrays, therefore they are not hunting you; stingrays physically can not eat you. I promise.

The Elasmodiver, a site that’s been a great resource to me both while writing this entry and just in general for my daily elasmobranch needs, actually has a page set up with information specifically related to this disturbing issue about stingray barbs, how to treat stingray injuries and information about stingrays relevant to beachgoers. I strongly recommend that everyone visit this if no other link provided here just to combat some of the rampant fear-based misinformation on stingrays that’s floating around.

Like all wild animals (which it is, make no mistake), it is good to treat stingrays with respect: don’t live in terror of them, do take precautions to not step on them (do the Stingray Shuffle!), don’t molest them, etc.

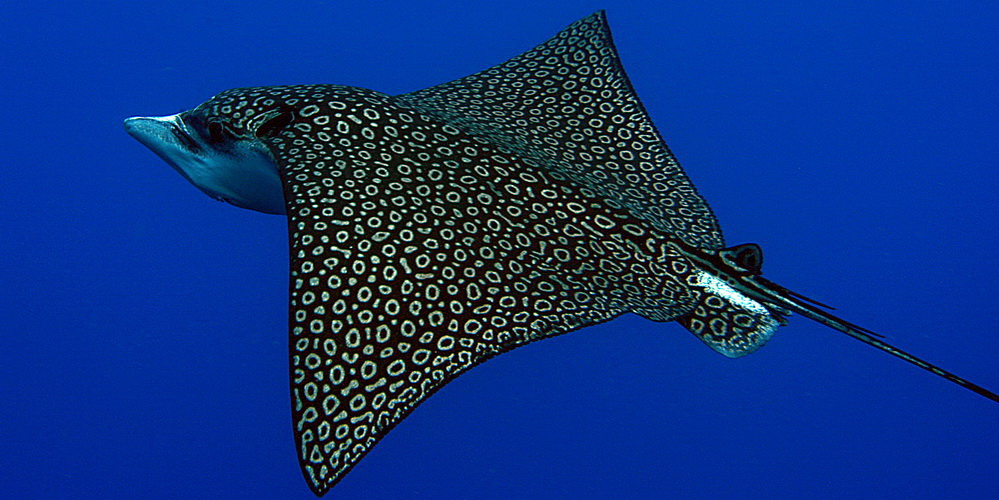

ANOTHER BEEF: YouTube commenters and members of the media are guilty of calling pretty much every batoid a “stingray” all the time. This is inaccurate and wrong: taxonomically speaking, stingrays must be members of the Dasyatidae family. There are LOTS of batoids that are not “stingrays”. Here are some examples of inaccurate reports about batoids in the media for an object lesson!Many of you may have seen news reports of a “giant stingray” leaping onto a woman in her boat some years ago. This “giant stingray” is clearly an eagle ray one of the most photogenic (and thus well-known) and large batoids. Please compare:

As you and anyone who has experience with rays can see, the two cannot be confused. It would be very odd if a stingray, a creature that dwells on the seafloor, randomly jumped into someone’s boat, as opposed to a ray of a species that frequently swims along the surface and is known for jumping.

To be fair, I do not expect every person to be able to identify every batoid, but instead of calling an unknown batoid a “stingray” (which is not a generic label. Sorry, the word “stingray” narrows it down a very specific set of rays!) perhaps they could just call it a ray? That’s not wrong, unless it’s not a ray. Which is possible, people call all sorts of things all sorts of wrong names all the time.

I will also take this opportunity to talk about Stingray City, a snorkeling/scuba diving site at Grand Cayman Island known for its stingray population that’s habituated to humans. If you’re bent on physically interacting with stingrays (which I guess is better than being terrified of them), this might be an option for you. Many well-known photographs of Southern stingrays are from this site.

They are tolerating you, not trying to become your friend: please be respectful towards them. They are not pets, do not treat them like your cat (unless your cat is a stingray). I assume that our readership knows better and would behave appropriately around rays, but some folks who have not been educated about how to behave around tame-ish wild animals do not.

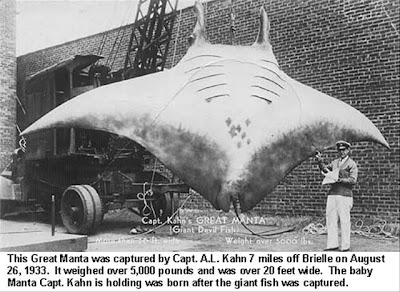

In conclusion: If you swim with the rays, or happen to encounter them in an unscheduled manner, don’t be That Guy.However, I will talk more about stingrays than just complain about those who do ill by them. Stingrays can get very large, as attested to in one of the photos up above.

The largest stingrays in the world are the freshwater stingrays that live in the rivers of Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia. They are the guys that show up in e-mail forwards from your relatives and websites that feature many exciting animated pop-up ads.

They are more formally known as freshwater whiprays and the binomial name is Himantura chaophraya. Yes, they are stingrays, meaning they have very large barbs on their tails. National Geographic has covered them as part of their Megafishes Project, which I naturally encourage you to check out because large weird freshwater fish are great. Jeremy Wade of Animal Planet’s River Monsters also did an episode on them if you enjoy that media modality.

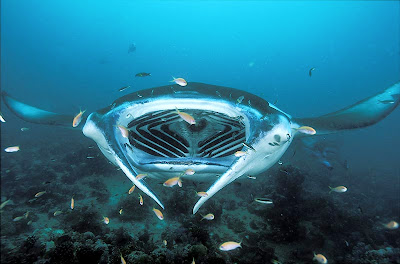

The largest ray, mantas are the charismatic megafauna of the batoid world. Behold their majestic form:

- The mouth is on the front of the head (not the bottom of the body)

- The prominent cephalic lobes, aka the sticky-out things on the front of their heads. Mobula rays (which look like small manta rays) also have these structures. Speaking of mobulas (which I will not talk much about, beyond saying that the two members* of family Mobulidae are mantas and mobulas, to give you an idea of their relationship), the Dive Shack Tides have produced a blog entry specifically about the mobulas of the Sea of Cortez for your viewing pleasure.

Here are mobulas doing their flying thing off Cabo Pulma:

Also, they school. A lot. They are somewhat photogenic.

- Their eyes are on the sides of their heads. While this isn’t as weird as the cephalic lobes or the the front-of-the-head mouth (this eye position is also present in eagle rays), stingrays’ eyes are on top of their heads.

- Like the largest of their non-flattened elasmobranch comrades, the whale shark, manta rays are also filter feeders. Unfortunately, the manta does not get to sport the natty grid + spots pattern that looks so cool on whale sharks. Now that I think about it, I’m surprised people don’t kill them to wear their skin, they do it to every other species unfortunate enough to have skin that is aesthetically pleasing to humans.

- While they are filter feeders, manta rays DO have teeth! However, they’re for reproductiontime, not for dinnertime. I actually reviewed this earlier when talking about batoid dentition, so scroll up if you want to see their little poky teeth.

Round 3: TORPEDO RAYS, aka ELECTRIC RAYS

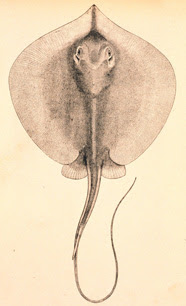

In addition to being pancakeoid, you’ll notice their tails (or more properly, “caudal fins”) more closely resemble those of fish than of stingrays or certainly mantas with their spindly tails. What are they used for? LOCOMOTION! Somehow this makes them look even sillier, the guy below vaguely looks like a living metal detector who just happens to be an awesome electric batoid. I doubt he is sympathetic to your gouty toe.

Electroreception (the biological ability to perceive electrical impulses) is not something unusual to elasmobranchs or to many fish in general; the platypus can do it, why can’t you? Electric rays are unique among rays in that they can both detect and emit electric impulses, an ability that is shared to a lesser extent by skates, though their electroreceptive organs differ in origin, function, strength, and location. Note that skates’ electrical discharges are too weak to be used for defensive or predatory functions.

Let’s break it down taxonomically. Technically, there’s no such “thing” as an electric ray, given that would imply that there is a single species called “the electric ray”. That is a blatant falsehood because there are actually about 60 species of rays that emit electricity.

Let me show you, because if you’re going to learn one thing from me it’s ridiculous fish taxonomy. Let’s do this thing:

Class: Chondrichthyes (Contains Elasmobranchii and Holocephali [chimaerae])

Subclass: Elasmobranchii (It’s a shark or a batoid!)

Order: Torpediniformes (Rays that do the electric thing)

Under the order Torpediniformes we get four families of electric ray with four evocative names: Narcinidae, Narkidae, Torpedinidae and Hypnidae. There may be a suggestion of a naming motif hidden here. Indeed, electricity-producing rays have been known to humans for a very long time and apparently used to be subject to medical employment.

I’ve found allusions to the ancient Greeks using electric rays as a form of anesthesia during childbirth (?!) but no reliable references because the Internet is full of lies. I have, however, found a letter from a guy doing experiments on electric rays writing to Benjamin Franklin about them in 1772 to tell him that he figured out that BY GOD THEY’RE FULL OF ELECTRICITY, JUST LIKE THAT LEYDEN JAR

Anyway, people have known about them for a while and used them for their busted toes and all kinds of weird stuff, with nary a thought for the ray’s welfare in mind.

BONUS: What do electric eels (which are actually really big knifefish, not eels at all) get for Christmas? Forced labor, depending on how liberal your definition of “labor” is.

So how strong is the shock of the electric ray, anyway? It kind of depends on which electric ray you’re talking about. As is so often the case with fish records, they vary and FishBase ain’t talking. The max seems to be about 200-220 volts and that seems to be pretty outstanding; the species cited as producing this was Torpedo nobiliana, the Atlantic torpedo. I look askance at records of things like 700 volts, which I have seen cited as an upper range figure.

There is a reason for the pancakeosity of the of the electric ray: if you observed the engraving by John Hunter above, electric rays’ kidney-shaped electricity-producing organs are located in the sides of their discs. If you’d like to see these organs in the flesh, the Brine Queen dissected an electric ray and documented the process.

An electric ray will specifically use its Thor-like powers to ambush its prey, wrap its flexible body around it to deliver powerful shocks, and then devour it using its distensible jaws. I’m not sure if the diver in this video got shocked, but the put out ray’s posture seems to suggest it at the very least entertained the notion:

I think this covers your introduction to batoids. There’s always more to say because there are a LOT of batoids: The ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research says that 55% of total extent elasmobranch species (sharks + batoids) are batoids, with around different 555-573 species of batoids. I’ve mentioned fewer than 10 species in this entry, to put it in perspective.

To conclude my entry, I’ll give a small bit of attention to the neglected skate. Skates are always neglected and I’ll fully admit I neglected them here. I blame the world for not having more information on skates and I blame skates for not being manta rays or having much of a reputation beyond, “How is it not a ray?”.

While no, they don’t get as big as river stingrays or mantas, they certainly can get big. I applaud the angler pictured below, Damian Greenwood, for releasing his quarry. There are definitely more sustainable fish to eat. Read the full write-up here.

Sharks and their kin–skates and rays–have remained essentially unchanged for hundreds of millions of years, and their very existence is now threatened by man and his fears. Thomas Allen takes us through the evolution of the shark, its folklore, its commercial uses, and gives us a detailed look at shark attacks–where they happen, why, and how to protect yourself from them. He describes over one hundred shark species–their behavior, appearance, size, and distribution–and provides helpful scientific illustrations. He offers current information on scientific research (including the recent studies on shark cartilage in cancer research), current population findings, and continuing conservation efforts.

With over twenty-five color photographs of familiar and unusual sharks, interesting and fact-filled sidebars, and useful appendices, THE SHARK ALMANAC is a comprehensive overview and the perfect book for anyone interested in these amazing creatures.

*=yes, I’m oversimplifying and excluding subspecies. DEALMadl, P & Yip, M. (2000). Essay about the electric organ discharge (eod) . Proceedings of the Cartilagenous fish Colloquial Meeting of Chondrichthyes , http://www.sbg.ac.at/ipk/avstudio/pierofun/ray/eod.htm