Well, my word, dear readers, it’s been a long time since we’ve last met! A bout of the flu kept us apart for two whole weeks, but we’re delighted to have the Free For All up and running again, and we are delighted to be returning on such an auspicious day!

In addition to celebrating National Poetry Month, as we have been all of April (sick or otherwise), it is also the observed birthday of William Shakespeare!

Historians don’t actually know for certain on what day Shakespeare was born. We know he was baptized in Holy Trinity Church in Stratford-upon-Avon on April 26, 1564, which leads us to conjecture that he was born on April 23rd, as newborns were typically baptized on the third day after their birth. His father was a prominent figure in Stratford, eventually rising to become bailiff (the highest official in the town). However, the family fortunes were not to remain good, and young William knew poverty as well as prosperity.

Again there isn’t a great deal of information about Shakespeare’s life. We do know he married Anne Hathaway, the daughter of a local farmer, in November 1582, when he was eighteen years old. Anne was pregnant with Susanna Shakespeare at the time of their marriage, and she was baptized on May 26, 1583. Their twins, Hamnet and Judith Shakespeare, were baptized on February 2, 1585.

We don’t know specifically when he began writing, but Shakespeare’s plays were being performed in London by 1592, and he was being attacked in the press as “an Upstart Crow” by playwright Robert Greene. You can see an etching of the Globe Theatre as it would have looked in Shakespeare’s time on the left. He remained involved in the London theater scene, both as a writer and a player (we are pretty sure he played Hamlet’s Father’s Ghost in the original production of Hamlet) until about 1613. Shakespeare died on April 23, 1616, at the age of 52, and his cause of death remains unknown. What we do know is that his work revolutionized not only theater, but English literature and poetry as a whole.

We don’t know specifically when he began writing, but Shakespeare’s plays were being performed in London by 1592, and he was being attacked in the press as “an Upstart Crow” by playwright Robert Greene. You can see an etching of the Globe Theatre as it would have looked in Shakespeare’s time on the left. He remained involved in the London theater scene, both as a writer and a player (we are pretty sure he played Hamlet’s Father’s Ghost in the original production of Hamlet) until about 1613. Shakespeare died on April 23, 1616, at the age of 52, and his cause of death remains unknown. What we do know is that his work revolutionized not only theater, but English literature and poetry as a whole.

Today, we are happy to bring you two of Shakespeare’s sonnets. Although the form existed well before Will, his development of iambic pentameter became such a signature that these poems are know as “Shakespearean Sonnets”. There are fourteen lines in a Shakespearean sonnet. The first twelve lines are divided into three quatrains with four lines each. In the three quatrains the poet establishes a theme or problem and then resolves it in the final two lines, called the couplet. The first twelve of these lines are divided into three quatrains with four lines each. In those three quatrains, Shakespeare (or the author of a Shakespearean sonnet) establishes a theme or problem and then resolves it in the final two rhyming lines, called the couplet.

The three quatrains are written in Iambic Pentameter. That means that each line contains ten syllables, and the syllables are divided into five pairs called iambs or iambic feet (an iamb is a metrical unit made up of one unstressed syllable followed by one stressed syllable, which you can hear in the way we say “Good BYE”). A line of iambic pentameter flows like this:

baBOOM / baBOOM / baBOOM / baBOOM / baBOOM.

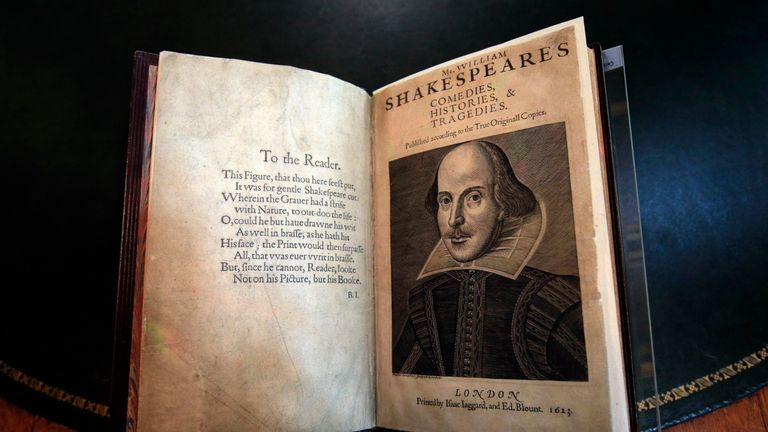

Shakespeare’s plays are also written primarily in iambic pentameter (some of which were first published in the First Folio of his works, pictured above), but the lines are unrhymed and not grouped into stanzas. Unrhymed iambic pentameter is called blank verse.

So, without further ado, here are two of Shakespeare’s sonnets–follow along with the iambic pentameter to learn about the structure of the poem, or simply enjoy the lovely language!

Sonnet 19: Devouring Time, blunt thou the lion’s paws

By William Shakespeare

Devouring Time, blunt thou the lion’s paws,

And make the earth devour her own sweet brood;

Pluck the keen teeth from the fierce tiger’s jaws,

And burn the long-liv’d Phoenix in her blood;

Make glad and sorry seasons as thou fleets,

And do whate’er thou wilt, swift-footed Time,

To the wide world and all her fading sweets;

But I forbid thee one more heinous crime:

O, carve not with the hours my love’s fair brow,

Nor draw no lines there with thine antique pen!

Him in thy course untainted do allow

For beauty’s pattern to succeeding men.

Yet do thy worst, old Time! Despite thy wrong

My love shall in my verse ever live young.

Sonnet 60: Like as the waves make towards the pebbl’d shore

By William Shakespeare

Like as the waves make towards the pebbl’d shore,

So do our minutes hasten to their end;

Each changing place with that which goes before,

In sequent toil all forwards do contend.

Nativity, once in the main of light,

Crawls to maturity, wherewith being crown’d,

Crooked eclipses ‘gainst his glory fight,

And Time that gave doth now his gift confound.

Time doth transfix the flourish set on youth

And delves the parallels in beauty’s brow,

Feeds on the rarities of nature’s truth,

And nothing stands but for his scythe to mow:

And yet to times in hope my verse shall stand,

Praising thy worth, despite his cruel hand.